Why High-Performing Leaders Feel Stuck

You've built a solid career. Your resume looks impressive. People ask for your advice. By most external measures, you're succeeding.

And yet something feels misaligned.

This disconnect shows up in different ways. Some leaders describe feeling like they're operating on autopilot—executing well but disconnected from any real sense of purpose. Others feel overwhelmed by competing demands, unable to identify which opportunities actually matter. Many simply feel tired, questioning whether the path they're on still fits who they've become.

The problem isn't a lack of ambition or capability. The problem is that most leaders operate without a clear framework for understanding what genuinely aligns with who they are and what they want to create. They're making decisions based on external expectations, past momentum, or what seems like the logical next step—without pausing to ask whether those choices connect to something deeper.

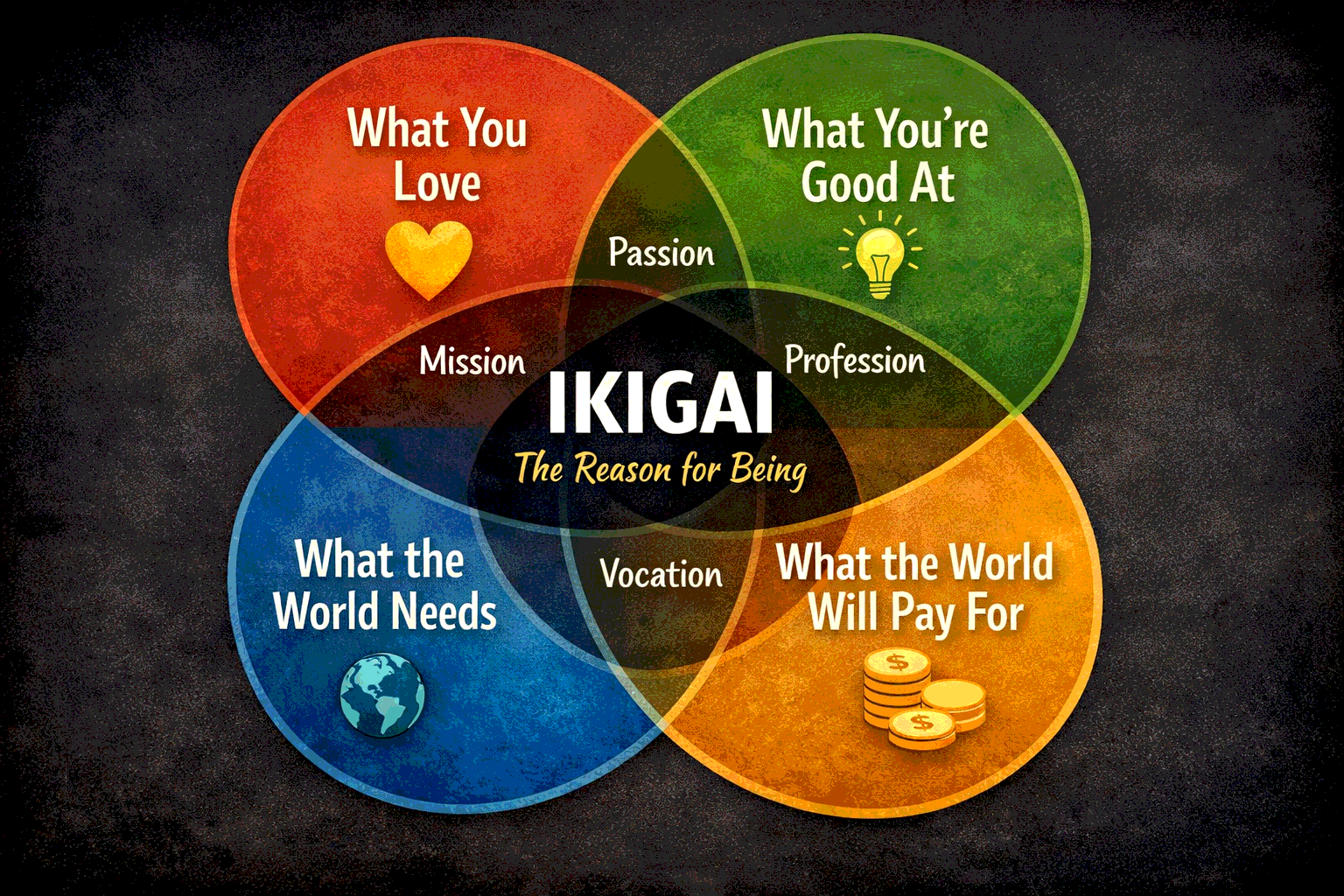

This is the time when I invite my coaching client to work with the Ikigai framework. Ikigai provides a structured way to reconnect with what actually matters to you. It helps you identify the intersection of what brings you energy, where your strengths lie, what problems you care about solving, and how you can create sustainable value.

One product leader used Ikigai, and it helped her discover that she was already working at the exact intersection of what she loved and what she was good at. Their challenge wasn't the role itself—it was how she was spending her time within that role. That single insight shifted everything about how she structured her days.

And yet something feels misaligned.

This disconnect shows up in different ways. Some leaders describe feeling like they're operating on autopilot—executing well but disconnected from any real sense of purpose. Others feel overwhelmed by competing demands, unable to identify which opportunities actually matter. Many simply feel tired, questioning whether the path they're on still fits who they've become.

The problem isn't a lack of ambition or capability. The problem is that most leaders operate without a clear framework for understanding what genuinely aligns with who they are and what they want to create. They're making decisions based on external expectations, past momentum, or what seems like the logical next step—without pausing to ask whether those choices connect to something deeper.

This is the time when I invite my coaching client to work with the Ikigai framework. Ikigai provides a structured way to reconnect with what actually matters to you. It helps you identify the intersection of what brings you energy, where your strengths lie, what problems you care about solving, and how you can create sustainable value.

One product leader used Ikigai, and it helped her discover that she was already working at the exact intersection of what she loved and what she was good at. Their challenge wasn't the role itself—it was how she was spending her time within that role. That single insight shifted everything about how she structured her days.

What Ikigai Really Means

Ikigai (生き甲斐) is a Japanese concept that roughly translates as "a reason for being" or "a reason to wake up in the morning." In its original cultural context, Ikigai refers to the small, everyday sources of meaning and joy—a morning walk, preparing a meal, time with family, work that serves your community.

The concept has been adapted in Western professional development into a four-part framework designed to bring clarity to complex career and life decisions. This adaptation focuses on four fundamental questions:

This four-circle framework has become popular precisely because it addresses something many leaders struggle with: understanding how personal fulfillment and professional contribution can coexist. When these four elements overlap, you've identified your Ikigai—the sweet spot where your internal drivers and external opportunities align.

A CTO I worked with realized through this process that his passion wasn't just technology. It was growing people. He had spent years optimizing systems and architecture, but what genuinely energized him were the conversations where he helped engineers see their own potential. That distinction became the foundation for how he restructured his leadership approach.

The concept has been adapted in Western professional development into a four-part framework designed to bring clarity to complex career and life decisions. This adaptation focuses on four fundamental questions:

- What you love – The activities, topics, or experiences that generate genuine energy and engagement

- What you're good at – Your natural strengths and developed competencies

- What the world needs – Real problems, gaps, or human needs that resonate with you

- What the world will pay for – Contributions others recognize as valuable enough to reward

This four-circle framework has become popular precisely because it addresses something many leaders struggle with: understanding how personal fulfillment and professional contribution can coexist. When these four elements overlap, you've identified your Ikigai—the sweet spot where your internal drivers and external opportunities align.

A CTO I worked with realized through this process that his passion wasn't just technology. It was growing people. He had spent years optimizing systems and architecture, but what genuinely energized him were the conversations where he helped engineers see their own potential. That distinction became the foundation for how he restructured his leadership approach.

How to Use Ikigai: A Four-Part Reflection

Ikigai is often presented as four circles to fill out, but that misses how the framework actually works. Each part builds on the previous one, creating a progression from internal clarity to external contribution.

Here's the logic:

This sequence matters because starting with external factors ("What does the world need?") often leads to answers based on obligation rather than authentic alignment. Starting with what you love creates a foundation of energy and motivation that sustains you through difficult decisions and challenging work.

The sections below walk through each part in detail, offering questions for reflection and showing how leaders have used these insights in practice.

Here's the logic:

- Start with energy – Identify what genuinely brings you alive

- Move to strengths – Recognize where joy meets competency

- Expand to contribution – Connect your strengths to problems that matter

- Anchor in value – Ensure your contribution creates a sustainable exchange

- Choose the next step – Turn insight into concrete action

This sequence matters because starting with external factors ("What does the world need?") often leads to answers based on obligation rather than authentic alignment. Starting with what you love creates a foundation of energy and motivation that sustains you through difficult decisions and challenging work.

The sections below walk through each part in detail, offering questions for reflection and showing how leaders have used these insights in practice.

Part 1: What You Love

When we talk about "what you love" in the context of Ikigai, we're not talking about hobbies or leisure activities—though those can provide clues. We're looking for the experiences that generate genuine aliveness, curiosity, and sustained engagement.

This shows up as:

Many leaders skip this reflection because it feels indulgent or impractical. But understanding what genuinely energizes you is one of the most practical things you can do. Energy is a finite resource. Knowing where yours comes from helps you make better decisions about where to invest your time and attention.

This shows up as:

- Activities where time seems to disappear

- Topics you find yourself reading about without being assigned to

- Conversations that leave you energized rather than drained

- Projects you volunteer for, even when your schedule is full

- Moments where you feel most like yourself

Many leaders skip this reflection because it feels indulgent or impractical. But understanding what genuinely energizes you is one of the most practical things you can do. Energy is a finite resource. Knowing where yours comes from helps you make better decisions about where to invest your time and attention.

Questions to explore:

Consider the digital transformation officer who realized through this reflection that what she loved wasn't implementing systems within large organizations—it was building things from scratch. She thrived in ambiguity, in the early stages where nothing existed yet and everything was possible. That insight became the first indicator that entrepreneurship might be her next move.

Your next step: Write one clear sentence: "What I love is..." Then spend a week noticing where this shows up in your daily work and life. Pay attention to the moments where you feel energized versus depleted.

- What activities or topics did you love as a child, before external expectations shaped your choices?

- When do you experience flow—complete absorption in what you're doing?

- What types of problems do you find yourself thinking about during downtime?

- If you could spend an entire day doing anything work-related, what would you choose?

- What parts of your current role do you look forward to?

Consider the digital transformation officer who realized through this reflection that what she loved wasn't implementing systems within large organizations—it was building things from scratch. She thrived in ambiguity, in the early stages where nothing existed yet and everything was possible. That insight became the first indicator that entrepreneurship might be her next move.

Your next step: Write one clear sentence: "What I love is..." Then spend a week noticing where this shows up in your daily work and life. Pay attention to the moments where you feel energized versus depleted.

Part 2: What You're Good At

Strengths are abilities you consistently deliver value with—whether they came naturally or through deliberate practice and development. Unlike "what you love," which focuses on energy and engagement, "what you're good at" focuses on demonstrated capability and reliable performance.

Some strengths emerge early and feel intuitive. Others develop over years of practice, becoming so refined that they eventually feel natural. A leader might have a natural talent for reading group dynamics, while their skill at financial modeling came from dedicated study and application.

Questions to explore:

This is where Ikigai starts to build on itself. Look for the overlap between Part 1 and Part 2—where what you love aligns with what you're good at. A CTO realized he wasn't just good at solving technical problems. He was exceptional at coaching engineers through complex challenges, helping them develop their thinking and build confidence. That strength had been present throughout his career, but he'd always seen it as secondary to his technical abilities. Recognizing it as a primary strength shifted how he designed his role and where he invested his development time.

Your next step: Write your sentence: "What I'm good at is..." Then notice this week where this strength shows up without effort. Where do you find yourself naturally stepping in or taking the lead?

Some strengths emerge early and feel intuitive. Others develop over years of practice, becoming so refined that they eventually feel natural. A leader might have a natural talent for reading group dynamics, while their skill at financial modeling came from dedicated study and application.

Questions to explore:

- What do colleagues, friends, or family members consistently ask for your help with?

- What tasks or projects do you complete more quickly or easily than most people?

- Where do you see patterns in your successes across different contexts?

- What feedback do you hear repeatedly in performance reviews or casual conversations?

- If you asked five people who know you well what you're exceptional at, what would they say?

This is where Ikigai starts to build on itself. Look for the overlap between Part 1 and Part 2—where what you love aligns with what you're good at. A CTO realized he wasn't just good at solving technical problems. He was exceptional at coaching engineers through complex challenges, helping them develop their thinking and build confidence. That strength had been present throughout his career, but he'd always seen it as secondary to his technical abilities. Recognizing it as a primary strength shifted how he designed his role and where he invested his development time.

Your next step: Write your sentence: "What I'm good at is..." Then notice this week where this strength shows up without effort. Where do you find yourself naturally stepping in or taking the lead?

Part 3: What the World Needs

This is where your internal clarity starts to connect with external contribution. "What the world needs" refers to real problems, gaps, or human experiences that resonate with you—not because you think you should care about them, but because you genuinely do.

This can operate at different scales:

The key is specificity. "The world needs better leadership" is too broad to be useful. "Organizations need leaders who can translate technical complexity into clear strategy" is specific enough to act on.

Questions to explore:

This part builds directly on Parts 1 and 2. You're looking for needs that connect to what you love and what you're good at—the places where who you are naturally aligns with what's needed.

A product leader realized her ability to simplify complexity was exactly what her organization desperately needed. The company was drowning in competing priorities, with every initiative labeled as urgent. Her next step wasn't finding a new role—it was protecting time for the strategic work that only she could do, rather than reacting to every incoming request.

Your next step: Complete the sentence: "What the world needs is..." Be specific about the world you're referring to—your team, your organization, your industry, a particular community.

This can operate at different scales:

- A problem your team or organization faces repeatedly

- A gap in your industry or professional community

- A challenge affecting a specific population you understand

- A broader societal need you feel equipped to address

The key is specificity. "The world needs better leadership" is too broad to be useful. "Organizations need leaders who can translate technical complexity into clear strategy" is specific enough to act on.

Questions to explore:

- What problems do you see repeatedly that frustrate you because they're solvable?

- Where do people come to you for help or perspective?

- What experiences from your own journey have given you unique insight into what others need?

- If you could solve one problem in your organization or industry, what would it be?

- What needs exist at the intersection of your experience and the communities you're part of?

This part builds directly on Parts 1 and 2. You're looking for needs that connect to what you love and what you're good at—the places where who you are naturally aligns with what's needed.

A product leader realized her ability to simplify complexity was exactly what her organization desperately needed. The company was drowning in competing priorities, with every initiative labeled as urgent. Her next step wasn't finding a new role—it was protecting time for the strategic work that only she could do, rather than reacting to every incoming request.

Your next step: Complete the sentence: "What the world needs is..." Be specific about the world you're referring to—your team, your organization, your industry, a particular community.

Part 4: What the World Will Pay For

This final piece is about sustainable value—the contribution that others recognize, trust, or reward. It's the difference between something you could do and something people actively seek out and exchange resources for.

"What the world will pay for" doesn't necessarily mean direct financial compensation, though it often does. It can also mean:

This element grounds Ikigai in reality. You might love painting, be good at it, and believe the world needs more art—but if no one values your specific artistic contribution enough to exchange resources for it, you haven't yet found sustainable alignment.

Questions to explore:

This part connects directly to Part 3. The world pays for contributions that solve real needs. The transformation officer I mentioned earlier noticed that senior leaders kept seeking her out for strategic clarity during periods of change. They valued that perspective enough that she recognized people would pay for it as a consulting service. That made leaving her corporate role feel logical rather than risky.

Your next step: Write down: "The value I create is..." Then consider: Am I being compensated fairly for this value? Is there a way to create this value more intentionally?

"What the world will pay for" doesn't necessarily mean direct financial compensation, though it often does. It can also mean:

- The contributions your organization values enough to create a role around

- Services people seek out and recommend to others

- Expertise people are willing to invest time to learn from

- Solutions that meaningfully improve outcomes people care about

This element grounds Ikigai in reality. You might love painting, be good at it, and believe the world needs more art—but if no one values your specific artistic contribution enough to exchange resources for it, you haven't yet found sustainable alignment.

Questions to explore:

- What do people currently pay you for (time, money, attention, opportunity)?

- Where do others see enough value in your work to recommend you or seek you out?

- What would people pay for if you offered it more intentionally or accessibly?

- Which of your contributions create measurable improvement for others?

- If you had to generate income from your skills tomorrow, what would you offer?

This part connects directly to Part 3. The world pays for contributions that solve real needs. The transformation officer I mentioned earlier noticed that senior leaders kept seeking her out for strategic clarity during periods of change. They valued that perspective enough that she recognized people would pay for it as a consulting service. That made leaving her corporate role feel logical rather than risky.

Your next step: Write down: "The value I create is..." Then consider: Am I being compensated fairly for this value? Is there a way to create this value more intentionally?

Putting It All Together: Your Ikigai Statement

When you complete all four parts, you have the building blocks of your Ikigai statement—a working description of where your energy, strengths, contribution, and value align.

This might look like:

"I love helping people see possibilities they hadn't considered. I'm good at asking questions that shift perspective and simplifying complex ideas into clear frameworks. The world needs leaders who can navigate ambiguity with clarity. People pay for strategic guidance during transitions and transformations."

Or:

"I love building systems that solve messy problems. I'm good at seeing patterns others miss and designing solutions that scale. Teams need someone who can translate between technical complexity and business value. Organizations invest in roles that bridge strategy and execution."

Your Ikigai statement is not a permanent declaration. It's a working hypothesis—a clear articulation of where you currently see alignment. As you grow, as your context changes, as new opportunities emerge, your Ikigai will evolve.

The purpose isn't to find one perfect answer. The purpose is to clarify what matters to you right now, so you can make better decisions about where to invest your time, energy, and attention.

This might look like:

"I love helping people see possibilities they hadn't considered. I'm good at asking questions that shift perspective and simplifying complex ideas into clear frameworks. The world needs leaders who can navigate ambiguity with clarity. People pay for strategic guidance during transitions and transformations."

Or:

"I love building systems that solve messy problems. I'm good at seeing patterns others miss and designing solutions that scale. Teams need someone who can translate between technical complexity and business value. Organizations invest in roles that bridge strategy and execution."

Your Ikigai statement is not a permanent declaration. It's a working hypothesis—a clear articulation of where you currently see alignment. As you grow, as your context changes, as new opportunities emerge, your Ikigai will evolve.

The purpose isn't to find one perfect answer. The purpose is to clarify what matters to you right now, so you can make better decisions about where to invest your time, energy, and attention.

Turning Insight Into Momentum

Understanding your Ikigai is useful. Acting on it is transformative.

Once you have clarity about where these four elements align, you can choose a concrete next step. This doesn't need to be dramatic—small shifts in how you work often create more sustainable change than complete career overhauls.

Your next step might be:

A small experiment – Test a hypothesis about your Ikigai by taking on a project, volunteering for an assignment, or offering your skills in a new context.

A conversation – Talk with your manager about restructuring your role to include more of what energizes you and less of what doesn't. Discuss how your strengths could be better utilized.

A shift in how you work – Redesign how you spend your time within your current role. Delegate or eliminate activities that drain you. Protect space for work that aligns with your Ikigai.

A boundary – Say no to opportunities that look good on paper but don't align with where you want to invest your energy.

A project to start – Launch something small on the side that allows you to explore an aspect of your Ikigai that your current role doesn't address.

The CTO who recognized his passion for growing people added dedicated coaching hours to his weekly schedule and declined some technical architecture projects. The product leader restructured her workload to focus on strategic simplification rather than tactical execution. The transformation officer began taking consulting projects while still employed, testing whether independent work would deliver the energy and meaning she anticipated.

Each of these steps was small. Each created momentum. Each was possible because they had clarity about where they were headed.

Once you have clarity about where these four elements align, you can choose a concrete next step. This doesn't need to be dramatic—small shifts in how you work often create more sustainable change than complete career overhauls.

Your next step might be:

A small experiment – Test a hypothesis about your Ikigai by taking on a project, volunteering for an assignment, or offering your skills in a new context.

A conversation – Talk with your manager about restructuring your role to include more of what energizes you and less of what doesn't. Discuss how your strengths could be better utilized.

A shift in how you work – Redesign how you spend your time within your current role. Delegate or eliminate activities that drain you. Protect space for work that aligns with your Ikigai.

A boundary – Say no to opportunities that look good on paper but don't align with where you want to invest your energy.

A project to start – Launch something small on the side that allows you to explore an aspect of your Ikigai that your current role doesn't address.

The CTO who recognized his passion for growing people added dedicated coaching hours to his weekly schedule and declined some technical architecture projects. The product leader restructured her workload to focus on strategic simplification rather than tactical execution. The transformation officer began taking consulting projects while still employed, testing whether independent work would deliver the energy and meaning she anticipated.

Each of these steps was small. Each created momentum. Each was possible because they had clarity about where they were headed.